français

english

Barbara Steinman, 2022 Paul-Émile-Borduas Prize

A pioneer in Quebec in the integration of video and multimedia into the field of visual arts, Barbara Steinman has left her unique mark on Quebec culture for more than 40 years. Through her installations, the Montreal artist deploys a sensory experience with multiple possibilities of interpretation, revealing her brilliant inventiveness. With some 30 personal exhibitions, more than 115 group exhibitions and 5 public works of art, she has earned recognition for the audacity and the depth of her artistic work. For more information: click here

The Paul- Emile-Borduas Prize is the most prestigious arts award (LaPresse) granted by the Government of Quebec for a remarkable contribution in the field of visual arts, fine crafts or digital arts in Quebec.

Barbara Steinman, prix Paul-Émile-Borduas 2022

Pionnière au Québec de l'intégration de la vidéo et du multimédia au champ des arts visuels, Barbara Steinman marque de son empreinte unique la culture québécoise depuis plus de 40 ans. Dans ses installations, l'artiste déploie une expérience sensorielle aux multiples possibilités d'interprétations, révélant sa brillante inventivité. Ses œuvres à la fois audacieuses et d'un grand raffinement ont été présentées dans une trentaine d'expositions personnelles et plus de 115 expositions collectives, et ce, tant au Québec et au Canada qu'à l'international. Pour en savoir plus: cliquez ici

Le prix Paul-Émile-Borduas est la plus haute distinction (LaPresse) attribuée à une personne pour sa contribution remarquable aux domaines des arts visuels, des métiers d'art ou des arts numériques au Québec.

BARBARA STEINMAN. Faire vivre les mots

Article publié dans

Vie des arts – n°271 – Été 2023

Par Léah Snider

Article published in

Vie des arts – n°271 – Summer 2023

By Léah Snider

(English text is not available)

Pionnière de la production vidéographique au Canada, Barbara Steinman est aujourd’hui reconnue pour son travail multidisciplinaire. La récente lauréate du prix Paul-Émile Borduas 2022 et moi avons pris part à une conversation autour des thèmes qui ont émergé au cœur de sa démarche, au fil des années. Portrait d’une artiste montréalaise aux œuvres marquantes.

RÉCITS CACHÉS

J’ai toujours été fascinée par la démarche de Barbara et par sa façon de l’investir à l’aide de médiums très différents : vidéo, photographie, néon, installation. Son travail implique une recherche constante, un processus qu’elle partage habilement en ayant le souci du mot juste et qu’elle sait livrer avec un véritable sens du récit. Quand on entre dans le studio de l’artiste, situé dans l’édifice Belgo à Montréal, on peut s’attendre à trouver une mise en scène d’images et de mots. Au cœur d’un montage de cartes postales, une citation de Roland Barthes retient notre attention : « In every old photograph lurks catastrophe (Dans toute photographie ancienne se cache la catastrophe) ». « Je sens qu’il y a quelque chose de contenu dans ces mots qui va apparaître… et que je vais soudainement comprendre… ! » me dit Barbara en riant.

L’artiste et moi avons discuté à de nombreuses occasions de son amour des liens imaginaires, de ce qu’elle perçoit comme des « coïncidences significatives ». Plusieurs thèmes dans son travail demeurent inaperçus – jusqu’à ce qu’ils soient énoncés (« unnoticed until spoken »), souligne-t-elle. En effet, lorsqu’on parle à l’artiste, chaque mot compte. On a l’intime sentiment d’être inclus dans une conversation d’où pourrait naître une image. Pour Barbara, tous les liens invisibles qui existent entre les faits, les idées, les gestes, les paroles peuvent mener à une œuvre. Le processus de création ne suit pas toujours une trajectoire logique : « Je dis souvent : “Remarquez ce que vous remarquez (Notice what you notice).” » Elle cite en exemple le point de départ de Reconfigurations (2009-2014), une série de photos créées en 2009 de façon imprévue à partir d’archives de son travail coupées en morceaux. « J’ai vu une pile de mes photos déchiquetées sur le sol et j’ai pris une photo. »

Pour l’artiste, le hasard est essentiel à sa création : « On doit lui laisser de l’espace. Ne pas l’éteindre. » Nul doute que Barbara fait parler les liens que l’on croyait muets. Jeune, elle voulait écrire des scénarios de films. « J’ai toujours été attirée par l’écriture et la scénarisation, mais je ne pense pas que j’aurais été douée pour ça. Je n’aime pas le temps linéaire. J’aime que les choses soient circulaires, tournées en spirale. »

Lors de sa formation en art vidéographique à Vancouver à la fin des années 1970, l’artiste exposait déjà brillamment cette réflexion sur le passage du temps1. Aujourd’hui, Barbara compte plus d’une trentaine d’expositions solo, et au-delà de cent quinze expositions collectives. Cet accomplissement a récemment été évoqué lors de la remise du prix Paul-Émile-Borduas 2022. La sensibilité et l’audace de son travail avaient également été soulignées en 2002, lorsqu’elle a reçu le Prix du Gouverneur général pour sa contribution exceptionnelle aux domaines des arts visuels et médiatiques. En 2015, l’Université Concordia à Montréal lui avait accordé un doctorat honorifique. Quand nous avions parlé de cette distinction il y a quelques années, Barbara m’avait confié combien elle se sentait reconnaissante pour le parcours professionnel qu’elle a eu la chance de connaître, et elle m’avait fait part de l’importance qu’elle accorde à Montréal comme lieu de création. « Montréal a toujours été ma ville, l’endroit où j’habite pleinement. »

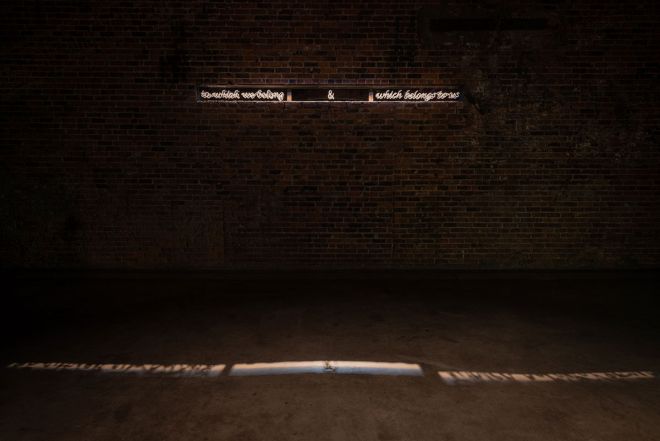

Cette notion d’appartenance, de home revient d’ailleurs régulièrement dans son travail. Elle s’est notamment traduite dans sa plus récente exposition à Montréal, qui a eu lieu à la Fonderie Darling, commissariée par Ji-Yoon Han. En s’inspirant du poème d’E. E. Cummings Dive for Dreams (qu’elle a transformé en Diving for Dreams), Barbara a reproduit avec des néons et des miroirs les mots « which belongs to us & to which we belong [qui nous appartienne et auquel nous appartenons] », une citation de Charles Moore sur la nécessité de se connecter à un endroit pour l’habiter entièrement. On retrouve ici la fascination de l’artiste pour le texte et la capacité des mots à traduire le monde sensible.

Cette œuvre se rapproche également de la série d’œuvres néon produite à partir de citations du Petit Prince d’Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. L’une d’elles, J’ai vu, une fois (2013), reprend un extrait du roman, tracé d’une écriture malhabile qui n’évoque en rien le ton autoritaire de l’affichage publicitaire et rappelle plutôt la graphie d’un enfant, dont la simplicité crée un effet d’intimité rarement ressenti à la vue d’un néon. Une lumière douce et presque feutrée émane de ces œuvres et nous éloigne du caractère voyant et agressif des enseignes lumineuses industrielles.

L’OMBRE PORTÉE

Les œuvres de Barbara ont toujours exprimé une fascination pour la lumière, ses reflets et ses ombres, autant dans son travail en vidéo que dans son art d’installation. Très petite, me rappelle-t-elle, elle a vécu dans une ville (Los Angeles) caractérisée par sa lumière. Puis, sa famille et elle sont retournées s’installer à Montréal, sa ville natale, connue pour son manque d’ensoleillement plus de six mois par an. Ce fut une expérience marquante. « Enfant, cela est devenu essentiel pour moi de comprendre et d’apprendre de la lumière et de sa profondeur. »

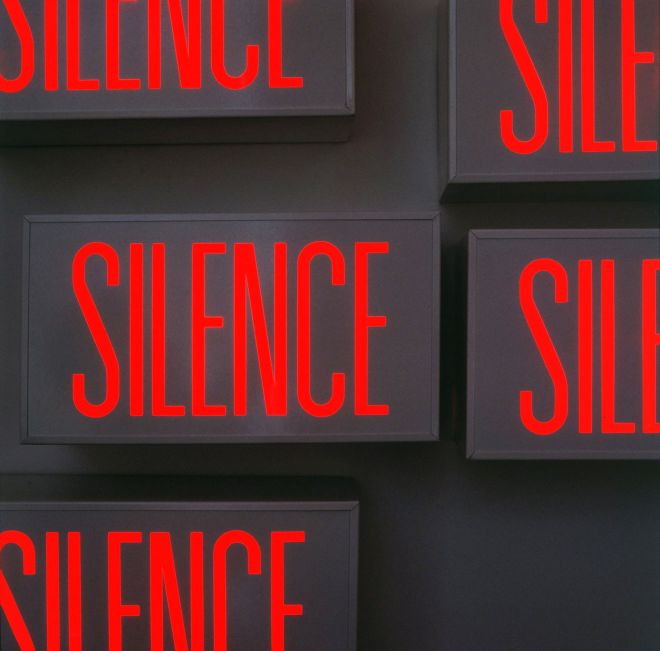

D’ailleurs, nombreuses sont ses œuvres où se donne à voir un jeu d’ombres. Lux (2000) en est un bel exemple. Les cristaux du lustre de style Empire, symbole du pouvoir, sont remplacés par des chaînes dont la force et le poids évoquent l’image puissante de la résistance. L’invisibilité sociale et la vulnérabilité ont toujours été des thèmes récurrents de sa démarche. C’est le cas dans SIGNS, commandée en 1992 à l’occasion de l’inauguration du Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal2. Pourrait-on penser ici que les histoires d’exil ont influencé son processus artistique ? « SILENCE », écrit en majuscules, au lieu de l’enseigne « SORTIE » semble faire référence au passé de sa famille, remontant aux pogroms, en Russie : « Ma grand-mère était la seule à raconter des histoires. Pour moi, il s’agit de mettre en lumière tout type de silence. Sommes-nous tous réduits au silence ou crions-nous collectivement – au point de ne plus rien entendre ? Annulons-nous les cris des uns et des autres ? »

À L’ÉCHELLE DE L’ESPACE PUBLIC

L’artiste travaille ingénieusement ces questions sensibles à plusieurs échelles. Située dans le hall d’entrée de l’ambassade canadienne à Berlin, l’œuvre d’art public La rivière (2005), composée de morceaux de granit et de quartzite incrustés, évoque un cours d’eau libéré des glaces, retrouvant enfin sa fluidité. Cette œuvre placée au cœur de l’espace, entre ce qui fut l’est et l’ouest de Berlin, nous fait prendre conscience de cette frontière qui s’imposait alors aux gens et de l’importance de ce lieu comme point de rupture.

« Pour moi, se confie-t-elle, c’est vraiment essentiel de toujours garder la même sensibilité dans mon travail, peu importe l’échelle – qu’il s’agisse de mettre en scène des créations dans une galerie de façon intimiste, ou de travailler à partir d’une œuvre d’art de grand format dans la sphère publique. J’essaie également de conserver une composante de plaisir qui, à mon avis, est très importante pour les œuvres d’art public. Nous partageons l’espace avec d’autres. Il faut être conscient de ce que l’on met en avant. » Barbara décrit toujours aussi habilement ses démarches, comme si elle voulait avant tout faire vivre les mots. Il existe un stade où l’œuvre nouvellement exposée appartient désormais aux autres, et c’est à ce moment que l’on doit la laisser vivre. « On se dit alors que c’est le mieux que l’on puisse faire », affirme-t-elle avec un sourire complice.

1 C’est au cours des années 1980, lorsqu’elle sera de retour à Montréal, que ses installations vidéo obtiendront

une reconnaissance internationale et seront présentées dans le cadre d’expositions et de biennales à Tokyo (1985),

São Paulo (1987), Venise (1988), Berlin (1989), Sydney (1990), puis à New York, au MoMA (1990).

2 Cette œuvre iconique a par la suite été exposée au Jewish Museum de New York, à Toronto, puis à Vancouver.

Barbara Steinman, lauréate du prix Borduas

Un honneur tardif tellement apprécié

(English text is not available)

L'artiste multidisciplinaire montréalaise Barbara Steinman est la lauréate du prix Paul-Émile-Borduas 2022, décerné par le gouvernement du Québec. Une reconnaissance qui lui fait très plaisir. La Presse l'a rencontrée au Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal (MABM) près de ses œuvres que le musée a acquises et expose dans deux pavillons.

Publié le 4 février Éric Clément La Presse

Barbara Steinman a eu 73 ans vendredi. C'est toujours une artiste élégante, éloquente, brillante et en pleine forme !

Elle est très touchée d'avoir reçu le prix Borduas, récompense la plus prestigieuse décernée par le Québec aux artistes visuels. Et reconnaissante, car il survient comme le couronnement tardif d'une carrière d'exception. Cette artiste conceptuelle - qui a fait des études en littérature à l'Université McGill et en arts médiatiques à l'Université Concordia - a surtout été honorée à l'extérieur du Québec, notamment par le prix du Gouverneur général en 2002.

Barbara Steinman n'a jamais été gratifiée d'une rétrospective au Québec. Étonnant quand on considère l'incroyable parcours de cette artiste. Expositions au MOMA, à New York, au Stedelijk Museum d'Amsterdam, au Tate Liverpool, au Musée des beaux-arts de l'Ontario et au Musée des beaux-arts du Canada (MBAC). En plus de participations à une expo internationale lors de la Biennale de Venise 1988 et aux biennales de Sydney, Séoul et São Paulo.

Ce sont ses années d'expérimentations à Vancouver qui ont mis au monde l'artiste Barbara Steinman. De 1974 à 1980, elle y a découvert le langage de la vidéo, devenant une des premières à l'incorporer dans des installations sculpturales. Elle y a fréquenté le dynamique centre d'artistes Western Front - qui fête ses 50 ans cette année - et réalisé des vidéos présentées notamment au Vancouver Art Gallery. Elle est revenue transformée à Montréal, où elle a dirigé Vidéo Véhicule, excroissance de l'ex-centre VéhiculeArt devenu PRIM en 1981, avant de prendre la direction de La Centrale galerie Powerhouse, de 1983 à 1985.

L'autre déclic de sa carrière aura été les Cent jours d'art contemporain de Montréal, organisés par Claude Gosselin. Elle y a exposé, en 1986, Cenotaphe, une œuvre sculpturale sur la disparition et l'exclusion, antérieurement créée pour une expo à Lyon. " Cenotaphe a été remarquée en Europe avant de l'être à Montréal, à São Paulo et en Allemagne, dit Barbara Steinman, dans un français impeccable. Le Musée des beaux-arts du Canada l'a acquise en 1987. "

L'engagement de Barbara Steinman s'est toujours exprimé de manière discrète, sans exubérance et sous les traits de concepts qu'il faut être prêt à déceler. Un style apprécié des amateurs de casse-tête visuel, ouvrant la porte de leur réceptivité. " Je me suis toujours donné pour mot d'ordre de m'adresser à la sensibilité des gens, dit-elle. Quels que soient leurs origines, leurs parcours et leurs histoires particulières. J'ose croire que c'est peut-être l'une des raisons qui ont fait que mes œuvres ont tant voyagé et été accueillies dans des contextes si divers, en Europe et en Amérique du Nord bien sûr, mais aussi en Asie, en Amérique latine et en Océanie. "

À la suite d'une visite à Prague où elle avait admiré de magnifiques lustres en cristal de Bohême, Barbara Steinman a eu l'idée de créer Lux, en 2000. L'installation évoque la notion de pouvoir, mais le cristal des élites éclairées a été remplacé par les chaînes d'acier des autorités brutales. Les cristaux sont au sol, où les ombres du lustre créent une cage éphémère. Une œuvre toujours d'actualité, acquise et exposée au MBAM.

L'artiste a eu ensuite la chance de croiser la commissaire montréalaise Ji-Yoon Han - qui prépare l'édition 2023 de la biennale montréalaise Momenta. Elle lui a permis, après des expos chez Pierre-François Ouellette, Roger Bellemare et Antoine Ertaskiran, de montrer son travail, en 2019, à la Fonderie Darling. Un travail sur la richesse et la vulnérabilité de l'humain, le credo de Barbara Steinman.

Barbara Steinman a aussi réalisé plusieurs projets d'art public. River, une œuvre in situ pour l'ambassade du Canada à Berlin en 2005, une autre pour l'ambassade du Canada à Moscou en 2010, et des œuvres extérieures à Toronto et à Vancouver. Elle prépare un solo à sa galeriste torontoise pour 2014 et expose, dès ce samedi (4 février), des photographies à la galerie TrépanierBaer, à Calgary.

Résiliente, Barbara Steinman a encore un grand besoin de créer. Elle rêve de participer à une expo collective avec des artistes québécoises de son époque. " Avec des femmes comme Geneviève Cadieux, Lyne Lapointe et Angela Grauerholz, qui ont toutes des œuvres dans les collections de nos musées, dit-elle. Car le temps passe. Durant la pandémie, j'ai réalisé que faire de l'art, penser, voir d'autres œuvres, ça ajoute une dimension essentielle à la vie. J'espère continuer le plus longtemps possible à m'exprimer à travers l'art. Car faire de l'art, c'est être proactif. "

VISCERAL MOMENTS

The body, the poetics of memory and the passage of time.

by Katherine Ylitalo,

gallerieswest, February 10 2023

(Le français n'est pas disponible)

Remarkable exhibitions by three major Canadian artists - Barbara Steinman, Geoffrey James and Evan Penny - are on view until March 4 at Calgary's TrépanierBaer gallery in conjunction with Exposure, Alberta's annual photography festival. Each solo show is a small gem encompassing a particular series that engages photography within the artist's larger practice.

Steinman's startling photographs of dying flowers encircle the main gallery and conjure an elegiac walled garden of unexpected beauty and grace. Desiccated cut flowers - mostly hybrid tea roses well past their prime - inhabit a velvety black space in unexpected ways. Some are arranged quietly, while others emerge from the darkness. Apricot-coloured petals fall freely in one composition and, in another, small dark-pink petals form a still cascade.

The exhibition, Keeping Time, was originally presented at Toronto's Olga Korper Gallery in 2021 and is remounted here. The images are arranged in small groupings that read like poems. Held to the wall by magnets, without frames or protective glass, they offer astonishing detail with unusual clarity and intimacy - whether the puckered tissue of a rose petal or drifting pollen from a white lisianthus.

The photographs were selected from hundreds that Steinman, a Montreal artist who received a Governor General's Award for Visual and Media Arts in 2002, produced when the pandemic lockdown prompted her to develop a new way of making art. Her daily studio practice became an antidote for difficult times. She collected discards from a local florist and organized them as a palette of colours in progressive stages of dehydration and fragility, learning how to handle them with care and experimenting with ways to structure compositions.

Underpinning each exhibition is the artist's regard for the photograph's physical presence. Collectively, the shows offer meditations on impermanence, the life of the body, the poetics of memory and the passage of time.

BARBARA STEINMAN: KEEPING TIME

(Le français n'est pas disponible)

Barbara Steinman: Keeping Time, photographic portfolio. Introduction by Zoë Tousignant, Border Crossings, Issue 159, 2022

For the past few years popular literature on psychology has been dominated by the notion that being connected to the present moment brings happiness. The vast number of books dedicated to the topic is evidence that it is not easy to cease focusing on what you cannot change (the past) and what you cannot control (the future). The challenge is greater still when the present moment is problematic when, for example, a global pandemic is forcing a complete reorganization of the way everyone lives and works. In times of heightened stress and uncertainty, disconnecting can be a way of surviving.

In September 2020, six months after the first lockdown was announced in Quebec, Montreal artist Barbara Steinman began her new series, Keeping Time, 2020-2021. Over the next few months, she produced several hundred photographs of flowers carefully posed or haphazardly placed against a black background. For a few hours every day, she would go to her studio and photograph the various stages in the life cycle of the cut flowers she acquired from a local florist. The act of making these images - of systematically spending time in the studio and applying the precise method selected - would become central to the work. The process, which included scrupulously noting the date and the type of flower depicted for each photograph, allowed the artist to give structure and meaning to an otherwise endless flow of undifferentiated days. Steinman explains: "As telling time became blurry, it was the changes in the flowers and trees around me that proved time was passing. This was reassuring. One day, looking at an exquisite flowering tree, I thought, ‘At least you're keeping time.'"

In the months before March 2020, Steinman had been preparing an exhibition for the Olga Korper Gallery in Toronto. When the show was postponed, she was left without a fixed deadline to work toward (or against). For many artists, deadlines for exhibitions, grant proposals and reports act as a motivating factor and an organizing principle in their practice. For Steinman, whose work is conceptual, multimedia and often site-specific, such time constraints are invariably accompanied by a series of technical and administrative obligations that require careful navigation. In making the series Keeping Time, she was able to take pleasure in an artistic process that was free from external pressures. As she describes it, the experience even had the effect of renewing her faith in being an artist.

A selection of images from the series was shown in June 2021. The images were predominantly roses, a species the artist was drawn to in part for their sometimes garish, artificially produced colours. The works were printed on very matte, fibrous paper chosen to give more depth to the black background and to enhance the delicate texture of the dehydrating blooms. Always arranged in vertical compositions, the flowers filled the frame, offering themselves in richly detailed close-up views as they bore silent witness to the progress of decomposition.

Businesses related to flowers were suffering because of the pandemic since, under normal circumstances, they relied heavily on special occasions and large social gatherings, like weddings and funerals. The cut flower industry's supply chain was also being compromised by the lockdown, which meant that imports, and therefore most flowers, were hard to come by. (A large proportion of the flowers sold in Canada are grown abroad, even though the country is also an important producer.) The donated specimens the artist was bringing back to her studio were past their prime and not saleable despite their newly acquired rarity. Seen as images whose subject was at the centre of an intricate global system and whose equilibrium was being seriously tested, Steinman's flowers appear more fragile still.

After presenting the works in exhibition, the artist received emails from viewers sharing their reactions. Many had clearly been moved by their visit and expressed appreciation of the palpable sense of tension between the delicate beauty and dark, mournful power conveyed by the images. Flowers have always been emblems of impermanence, and Steinman's are no exception: as photographs of singular fragments of time, they celebrate a particular stage in a life cycle, while pointing to impending demise. It may be that these works gave visitors to the exhibition an opportunity to connect to the moment pictured, but also to the moment of the visit itself. Such an experience of presentness, as difficult as it may be to achieve and sustain, possibly offers the interior space in which to process the overwhelming sense of grief that has permeated the past two years. And coping with grief cannot be rushed. It takes time.

Zoë Tousignant is a photography historian based in Montreal. She is the curator of photography at the McCord Museum.

BARBARA STEINMAN AT DARLING FOUNDRY

( Diving for Dreams at the Darling Foundry)

By James D. Campbell, August 2019

Barbara Steinman has activated the main exhibition space here with an unusually spare and eloquent installation. She has transformed the space into an equilateral triangle and luminous palimpsest. The Montreal-based artist began her career in Vancouver as a video artist and has since been celebrated for the excellence of her multidisciplinary work. Working here at the top of her form, the artist lures viewers into a seamless consideration of issues involving architecture, home and, not least, constituting alterity.

In Diving for Dreams, which also serves as the title of the whole exhibition, five simple neon drawings are installed on three sections of an interior wall painted in the liminal hue of robin's egg-blue. These delicate light interventions around the perimeter of the Main Hall are pure poetry. The simplicity is deliberate and evokes folk art and children’s art and even art brut with stripped-down images of a baying wolf, hearth and home, heart, bed or divan, bird of prey. Steinman collated some of these outlines from immediate renderings she had asked people to make in response to their idea of ‘home’. She then executed a series of neon graffiti works that freely integrated those almost pictographic renderings as core subject matter -- and they stand as a source of authentic distillation of communal discourse.

In Niche, Steinman made use of a lucky find: the crevice on the towering back brick wall of the space. She installed a mirrored rectilinear glass panel. Letters in white glass meander across the reflecting surface: "to which we belong & which belongs to us". The suggestion of ownership and home and belonging is a thematic opening wedge that in fact unified the entire exhibition. We live in an economic climate where most 30-year-old Canadians are far less likely to own their own home than their baby boomer parents did at the same age. The national home ownership rate is in a state of continuing decline. Being at home, therefore, is related less to having a fixed abode and more to transitory, partial and provisional relationships with where we live. As is her usual wont, Steinman opens the parentheses on this phenomenon without recourse to aesthetic shock therapy. But the effect is no less profound, no less revelatory.

Niche, 2019. credit Christine Guest

Day and Night (1989) is the third facet of the exhibition. It is a powerful series of four staged photographs in light boxes. They depict an anonymous figure sheltering in the recessed alcove of an industrial building like the Darling Foundry in its earlier incarnation. It was originally executed specifically for the space above the atrium of the contemporary galleries at the National Gallery of Canada. It has now been removed from that context and stands on the floor plane here at specific intervals. Writing for another publication on Steinman’s Study for the Installation “Day and Night” a few years ago, I noted that she dilates with acuity on the nature of a shared social reality. In fact, Day and Night is a profound meditation on homelessness by an artist who has always been attentive to the fate of the disenfranchised and the dispossessed. It is especially fitting because it is iconic for her practice of four decades and is not dated in any way. It is a piece of philosophical reparation for those whom history has hurt. Installed on the floor instead of lifted up on the wall plane, the large heartrending images provide a sort of moral weight for the more whimsical renderings in neon that shine down from above. Certainly, these light boxes have all the wherewithal we have come to expect of her practice before and since, and they are just as compelling as anything we have seen over the years by Jeff Wall, including his latest works at Gagosian.

Steinman works seamlessly and stealthily across the surface of things, a sort of covert operative on the go, searching out and assessing sites that she can palpate and bend to her purpose as a politically engaged artist. Yet her work is also profoundly chameleon and is less anchored in the specificity of given place than in a dynamic reflection on migration, home and the liminal. The exhibition transforms the former foundry into a metaphorical shelter safeguarding the promise of those left by the wayside of the historical process in a cascade of litanies that forms a potent critique of economic oppression and power relations.

Daring Others (Photo Souvenir) is a fitting coda for the show. Near the exit, visitors are invited to take home a postcard with an image of the facade of the Darling Brothers Foundry, referencing the original function of the building, and reversing polarities, so to speak, so that it is seen with all its attrition and effacement on display. It is ironic and clever and strangely numinous ephemera.

Writing on Steinman’s work 30 years ago, I quoted Frederic Jameson, the American literary critic, philosopher and Marxist political theorist of distinction. His words are as relevant to her endeavour now as they were then:

“History is what hurts, it is what refuses desire and sets inexorable limits to individual as well as collective praxis, which its 'ruses' turn into grisly and ironic reversals of their overt intention. But this can be apprehended only through its effects, and never directly as some reified force. This is indeed the ultimate sense in which History as ground and untranscendable horizon needs no particular theoretical justification; we may be sure that its alienating necessities will not forget us, however much we might prefer to ignore them.' [1]

Yes, history is what hurts and Steinman – in a voice never strident, sometimes elliptical, always radiant -- critiques the alienating necessities of History precisely so as to reclaim in present discourse those that History has estranged and dispossessed. She effectively memorialises subjects denied a common name, a concrete identity, a reasonable life. She has a savvy and acute political consciousness and her hugely sophisticated installations are socially symbolic acts. The works exhibited here are as luminous and nourishing as starlight on a clear night.

Barbara Steinman in the Darling Foundry, 2019.

1. James D. Campbell, “History Hurts: Barbara Steinman and Installation as a Socially Symbolic Act” in ” C Magazine # 22, Summer 1989

Campbell, James D., Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art, New York, NY, August 2019

GYMNASTIQUE CÉRÉBRALE À LA FONDERIE DARLING

( Diving for Dreams à la Fonderie Darling)

par Éric Clément, le 30 juin 2019

C'est à Ji-Yoon Han que l'on doit l'expo de Steinman. La commissaire d'origine coréenne avait souhaité confronter l'artiste montréalaise aux vastes espaces de la grande salle de la Fonderie Darling. Barbara Steinman a accepté le défi. Tant mieux, car ses apparitions se font rares. La lauréate du prix du Gouverneur général (en 2002), aujourd'hui représentée par les galeries torontoise et parisienne d'Olga Korper et de Françoise Paviot, a déjà présenté son travail dans des écrins tels que le Museum of Modern Art de New York, le Stedelijk d'Amsterdam, le musée Reina Sofía de Madrid ou encore le Musée d'art métropolitain de Séoul.

À la Fonderie, elle a su, avec intelligence, faire parler l'espace industriel en s'inspirant du poème Dive for Dreams d'E.E. Cummings, qui incite à se dégager des modes, diktats médiatiques et idées reçues, pour conserver un minimum d'authenticité. Dive for Dreams est devenu Diving for Dreams, constituée de quatre oeuvres qui habillent les contours de la salle, laissant le visiteur aller et venir dans l'espace central.

Dans un trou du vieux mur de briques, Barbara Steinman a réalisé Niche, avec néons et miroirs, et les mots which belongs to us & to which we belong (un endroit qui nous appartienne et à qui nous appartenons), une citation de Charles Moore sur la nécessité de se connecter à un endroit pour l'habiter pleinement. Une oeuvre à voir de préférence en fin de journée pour profiter de la lumière qui s'y réfléchit (le centre d'art est ouvert jusqu'à 22 h les jeudis).

Niche, 2019. crédit Christine Guest

L'expo comprend Jour et nuit, une série de quatre photographies que Barbara Steinman a conçue en 1989 pour le Musée des beaux-arts du Canada. Les images sont celles d'une femme ayant trouvé refuge dans le chambranle de la porte d'un édifice. Des images qui suggèrent la dichotomie entre développement urbain et éviction sociale, un phénomène qui, justement, s'amplifie dans le quartier de la Fonderie, où des immeubles d'habitation transforment en profondeur le tissu social local.

Enfin, comme dernière intervention, Barbara Steinman a créé une carte postale (offerte au visiteur) avec une image de la façade de la Fonderie Darling dont les mots « Darling Brothers Foundry » ont été altérés pour donner « Daring Others ». Une invitation à l'audace ou à l'idée que les frères Darling (dont la fonderie a été en activité pendant un siècle) étaient téméraires.

Cette expo sur la tentative d'établir une connexion de proximité avec des lieux est à l'image de l'oeuvre de Barbara Steinman, qui plonge au fond du rêve, certes, mais tout en célébrant la mémoire et le produit du génie humain.

Barbara Steinman à la Fonderie Darling, 2019.

Clément, Éric, Arts visuels, La Presse, Montréal, Publié le 30 juin 2019.

Shards: Compact Disc, No. 1, 2013. Chromogenic print 42" x 57.75"

RECONFIGURATIONS: CREATIVE CONTINUITY

by Mark A. Cheetham

There is an adage that the beginnings of new work are always to be found in an artist’s previous efforts. The artwriter Adrian Stokes (1902-72) underlined the intertwined psychological and material complexity of this seeming truism: “We have our ways and means of keeping things alive: we forget nothing; and the deeper sources of our feeling are tapped by our environment.... The external world is the instigator of memory: the external world reflects every facet of the past: it is the past rolled into the present.” 1 Steinman’s ‘reconfigurations’ - her strands, shards, and magnetic tapes - began as an attempt to purge her archive of documentation on of her earlier work. This process took an unexpectedly positive turn. As she writes, “the ‘Strands’ series … is the afterlife of the process of destroying pictures.” [1] The externalization and distortion of her past artistic production accidentally revealed a line running through her work, her employment at different times and in different contexts of photography, digital information on stored on disks, and VHS tape. As Steinman specifies, she realized that “glass, light and the dimension of time have been recurring elements in my work since my earliest video and multi media installations.”

Steinman’s work is anything but predictable, ranging as it does from politically charged installation work to neon text pieces to outdoor public art; the photographic series in this exhibition are surprising and nuanced but also work to extend the process of reconfiguration that she recently discovered.

We can imagine that Steinman’s first recognition of the significance of the shredded, crushed, or tangled materials that she had sought to discard was an epiphany of continuity, of “the past … rolled into the present.” If this new work was par ally foretold in a recognizable but nonetheless individual way, Steinman also unintentionally participates in one of the founding legends of artistic creativity, that one can capitalize on the fleeting strangeness of one’s own production. A relevant example is Wassily Kandinsky’s claim in “Reminiscences” (1913) that he saw the way into abstraction by misrecognizing as revolutionary one of his own paintings that he had casually placed sideways against a wall in his studio.

In their visual precision and lushness, the elements reconfigured in these photographs insist on the present moment of a viewer’s contemplation. We have to be struck by the detail made visible, the marks of shredding, crushing, or tangling for example, and by the emerging richness of colour, tonality, and texture. In a renewed but also for Steinman a typical manner, the simplicity of what we see discloses nothing less than creativity in action, the mute but startling negotiation of inner and outer environments, of the personal and cultural past and present.

Cheetham, Mark. A., Reconfigurations: Creative Continuity in: Reconfigurations, Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto, 2013.

1. Adrian Stokes, Inside Out: An Essay in the Psychology and Aesthetic Appeal of Space (1947). In England and its aesthetes: biography and taste / John Ruskin, Walter Pater, Adrian Stokes, essays; commentary, David Carrier. Amsterdam: G+B Arts International, 1997. 95.

RECONFIGURATIONS : LA CONTINUITÉ DANS LA CRÉATION

par Mark A. Cheetham

Il est dit que toute œuvre nouvelle porte les traces des réalisations antérieures de l'artiste. L’écrivain et historien d’art Adrian Stokes (1902-1972) a commenté la complexité de cette idée en insistant sur les liens indissociables entre psychologie et matérialité : « Nous avons nos façons et nos moyens de maintenir les choses en vie : nous n’oublions rien, et nos sentiments, à leurs sources les plus profondes, sont stimulés par notre environnement [...] Le monde extérieur est l'instigateur de la mémoire; le monde extérieur reflète chacune des facettes du passé puisque le passé s’y imbrique au présent. »

Les Reconfigurations de Barbara Steinman – les chutes de papiers (Strands), les éclats de disque (Shards), et les bandes magnétiques (Tapes) – sont issues du désir de l’artiste de purger les archives qui ont documenté ses œuvres antérieures. Un processus qui a pris une tournure inattendue et finalement positive. Selon l’artiste, « la série Strands... c’est la régénérescence née du processus de destruction des images.» L'externalisation et la distorsion de sa production artistique antérieure lui ont permis d’éclairer différemment la ligne directrice de son travail, suivant qu’elle employait, à des moments distincts et dans des contextes différents, la photographie, l'information numérique stockée sur des disques et ou des cassettes VHS. Elle a ainsi constaté : « le verre, la lumière et la dimension du temps ont été des éléments récurrents dans mon travail dès ma première vidéo et mes premières installations multimédias. »

Le travail de Steinman est tout sauf prévisible, allant d'installations à connotation politique, à des œuvres-textes en néon ou des œuvres publiques. Les séries photographiques de cette exposition, qui lui ont permis d’approfondir ce processus de reconfiguration récemment découvert, sont donc aussi surprenantes que nuancées.

Le moment où Steinman prit conscience de la signification de ces matériaux déchiquetés, endommagés, ou entremêlés - ceux qu'elle avait compté jeter – peut facilement être imaginé comme une épiphanie de la continuité, du « passé... qui s’imbrique au présent. » Grâce à l’unicité de l’œuvre, combinée à son caractère partiellement reconnaissable, Steinman participe également, peut-être sans même le savoir, à l'un des mythes fondateurs de la créativité artistique, soit l’idée que l'on puisse tirer profit d’une impression d’étrangeté passagère face à sa propre production. Pensons à Wassily Kandinsky, qui dans Souvenirs (1913), affirme avoir été appelé vers l'abstraction dans un instant où, ne pouvant reconnaître l’une de ses propres toiles qui était placée à un angle fortuit dans son atelier, la prit pour une œuvre absolument révolutionnaire!

Dans leur précision visuelle et leur luxuriance, les éléments reconfigurés dans ces photographies appellent le regardeur à contempler le moment présent. On ne peut s’empêcher d’être frappé par la révélation des détails : les marques du déchiquetage, de la destruction et de l’entremêlement, la richesse émergente de la couleur, de la tonalité et de la texture. De manière renouvelée, mais aussi tout à fait typique de Steinman, ce qui est donné au regard n’est rien de moins que la créativité en action, la négociation tranquille, quoique toujours émouvante, entre l'environnement intérieur et extérieur, entre le personnel et le culturel, le passé et le présent.

Traduit de l’anglais par Léah Snider.

Cheetham, Mark. A., RECONFIGURATIONS : La Continuité dans la création dans: Reconfigurations, Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto, 2013

1. Adrian Stokes, «Inside Out: An Essay in the Psychology and Aesthetic Appeal of Space.», 1947, dans England and its aesthetes: biography and taste, John Ruskin, Walter Pater, Adrian Stokes, essais; commentaires, David Carrier, Amsterdam : G+B Arts International, 1997.

Signs, 1992. Detail. 60 painted light boxes, programmed. 20 x 38 x 17 cm each